Hello and welcome to Issue 02.2 of Multitudes.

Written by me, Stephanie Zeller.

✨ Happy Almost Halloween! If you’ve already subscribed: Hey! Hello! Thanks for being here. If you haven’t: I forgive you, but good news: you have endless opportunities to do so!

Though I’m not a wholesale proponent of Stoicism, especially the principles that deal with personal emotional control, I have continuously returned to portions of its framework in strange times both past and present. Each day I speak to scientists around the world about their fire, drought, ice, and ocean data, helping them identify and analyze alarming global climate trends. Marcus Aurelius’s writings have proved especially pertinent and have provided some personal solace in the face of worsening climate-related disasters.

ALSO: DON’T FORGET TO VOTE!

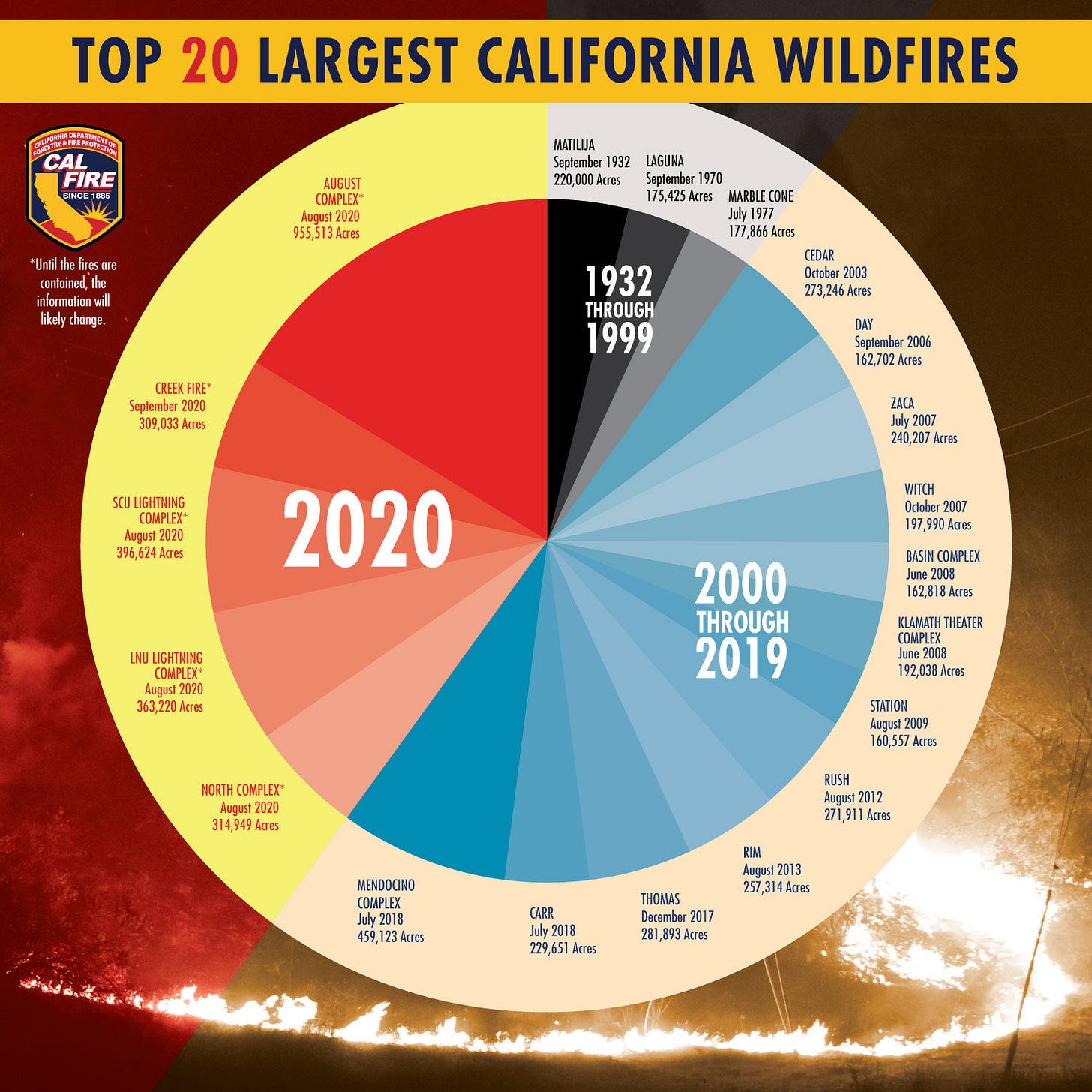

As of August 31, over one third of California’s largest and most destructive fires have occurred in 2020.

Top 20 largest California wildfires since 1932. Image courtesy of CalFire.

This year has set record after unfortunate record: uncontrollable Australian brushfires killed over one billion wild animals, Greenland’s ice sheet began losing ice at its fastest rate in over 12,000 years, and we’re on track to have the worst hurricane season (the most named storms) since we began counting. (The worst on record so far is 2005, with 28 named storms.)

The fires have been worsened by increasingly widespread drought and sporadic rainfall, the storms by rapidly warming and acidifying oceans. These newly volatile oceans are also partially to blame for Antarctica’s staggering ice loss in the 21st century—literally billions of tons per year, according to recent research—which will further destabilize vulnerable ecosystems, disrupt global current systems, and continue to raise sea levels.

Sea level rise is predicted to displace at least 190 million people by 2100, which will contribute, along with fires and storms, to mass climate migration, further stressing global economies, resources, arable land, and infrastructure.

Compounding effects of climate change are not disconnected from the recent increase in highly contagious disease outbreaks. In fact, humans have understood the relationship between climate and health since before the common era: though victory was within his grasp, Hannibal declined to invade Rome due to the threat of seasonal malaria, sparing the empire for another 150 years.

We live in a time of mutually amplifying disasters—the result of several generations of federal mistakes, willful ignorance, and rushed industrialization—and are now tasked not only with adjusting to new realities, but with building a better world. The latter often seems easier than the former, perhaps because world-building must be a group effort, while adjusting to new realities—that burden falls on each of us, as individuals.

Long after Hannibal’s harrowing journey over the Alps and subsequent failed conquest of Rome, Marcus Aurelius reigned emperor, and gained the moniker “Philosopher King” for his writings on coping with unhappy realities.

Marcus Aurelius is one of the three primary proponents of late Stoicism. Conceived in the third century AD, Stoicism attempted to provide a unified account of the world, constructed from logic and virtue ethics—ethical theories which emphasize self control, good character, and a sense of honesty.

Stoicism’s most recognizable tenet is also the root of our modern definition for stoic: while you cannot control what happens to you, you can control your actions. To the Stoics, an evil, amoral person lacked self control and was wholly subject to their every emotional whim.

The writings of the first Stoics have been lost, so we largely have those of the prominent late Stoics—Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, and Seneca—by which to understand its conceptual roots. Aurelius and Epictetus represent two ends of the social spectrum: the former, a ruler of one of the greatest empires in human history; the latter, a slave and indigent outcast.

These two men faced drastically different hardships, yet both diligently subscribed and contributed to the same school of philosophical thought. Epictetus came before Aurelius, so his teachings and writings likely influenced the emperor’s approach to stoicism.

(This context is important because, though Aurelius’s position would have come with its own challenges, he lived a fairly privileged life and wouldn’t have faced starvation or abuse as Epictetus did. However, as pure conjecture, absorbing Epictetus’s teachings may have given Aurelius a broader perspective on hardship, perhaps making him a more competent ruler.)

One of Marcus Aurelius’s most famous and influential works was never intended for public distribution. Meditations, a remarkable collection of insights into human nature, responsibility, death, life, emotional and physical hardship, and governing an empire, was Aurelius’s personal journal.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. Book cover courtesy of Penguin Publishing Group.

“Reflect on the yawning gulf of past and future time, in which all things vanish. So in all this it must be folly for anyone to be puffed with ambition, racked in struggle, or indignant at his lot—as if this was anything lasting or likely to trouble him for long.” (Book 5, 23)

His entries reveal a deep respect for Stoic teachings and an earnest desire to apply them to his life and to his work. Strikingly, the “yawning gulf” between Aurelius’s time and our own has not diminished the relevance of his words, nor do we now face moral struggles so different from those of he and his contemporaries nearly 2,000 years ago.

“I travel on by nature’s path until I fall and find rest, breathing my last into that air from which I draw my daily breath, and falling on that earth which gave my father his seed, my mother her blood, my nurse her milk; the earth which for so many years has fed and watered me day by day; the earth which bears my tread and all the ways in which I abuse her.” (Book 5, 4)

As the familiar earth of Aurelius’s time fades forever from our own, his stoic meditations provide both a salve and a charge for moving forward into ever stranger times. As upsetting and jarring as this climate transition will be, rather than devolving into collective dissonance or collective panic, we can choose to accept each moment with humility, determination, and gratitude.

“‘It is my bad luck that this has happened to me.’ No, you should rather say: ‘It is my good luck that, although this has happened to me, I can bear it […] neither crushed by the present nor fearful of the future.’ [...] So in all future events which might induce sadness remember to call on this principle: ‘This is no misfortune, but to bear it true to yourself is good fortune.’” (Book 4, 49-49.2)

Aurelius pairs this reframing of hardship and worry for the future with several passages on a person’s duty to their contemporaries and to nature. He seemed to understand well before our satellites and data and modeling the systemic character of the natural world and how we, as humans, fit into that system.

“Think always of the universe as one living creature, comprising one substance and one soul: how all is absorbed into this one consciousness; how a single impulse governs all its actions; how all things collaborate in all that happens; the very web and mesh of it all.” (Book 4, 40)

“We all work together to the same end. [...] One person contributes in this way, another in that. [...] What of each of the stars? Is it not that they are different, but work together to the same end?” (Book 6, 42-43)

“Can you not see plants, birds, ants, spiders, bees all doing their own work, each helping in their own way to order the world?” (Book 5, 1)

In the face of irreversible destruction, of feeling completely ineffectual, small, or crushed as forests burn rampantly, entire regions are swallowed by warming seas, reefs die off, and food chains crumble, Marcus Aurelius reminds us to take existence day by day and to be an active part of the greater whole.

“Love the art which you have learnt, and take comfort in it.” (Book 4, 31)

“You must compose your life action by action, and be satisfied if each action achieves its own end as best can be. [...] Gladly accept the obstruction as it is, make a judicious change to meet the given circumstance, and another action will immediately substitute and fit into the composition of your life. Accept humbly: let go easily. [...] Remind yourself that it is neither the future nor the past which weighs on you, but always the present.” (Book 8, 32-33, 36)

We cannot control when we were born, who shares our timeline, or which problems we must face. According to the Stoics, we can only be grateful for what we have, work earnestly to apply ourselves to the crises of our time for the collective good, and value those who share our journey.

“Fit yourself for the matters which have fallen to your lot, and love these people among whom destiny has cast you.” (Book 6, 39)

To conclude, a powerful modern parallel and example of applied stoic principles comes from a towering political philosopher and cultural luminary, the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Her response when asked how she would want to be remembered:

“Someone who used whatever talent she had to do her work to the very best of her ability. And to help repair tears in her society, to make things a little better through the use of whatever ability she has.”

In Case You Missed It: Check out these previous issues of Multitudes!

02.1: Combatting Misinformation with Empathy

“People talk about a hierarchy of expertise, knowledge, power, control…we’re constantly trying to find ways to balance that,” said David Ring, MD, PhD, principal investigator, Associate Dean for Comprehensive Care and Professor of Surgery at the Dell Medical School. “We don't want people to feel that we don't care, to feel dismissed, to feel that we’re belittling their concerns or that we’re being arrogant, and yet, [according to our research], they do.”

01.2: The Future of Science Visualization is in the Arts

Thousands of years before humans created the first orbiting laboratory, allowing a select few to live, work, and witness our perfectly average star envelop in sheets of gold our little blue marble many times per day, year-round, there was Eratosthenes. Born in 276 BCE in Cyrene, Lybia, Eratosthenes not only created a mathematical proof that the earth is round but also accurately measured its circumference.

Hi there! Thanks for reading. If you like what I’m doing here, you should tell your friends. If you’re interested in keeping up with me, you can find me on Twitter @StellerZeller, or on Instagram, @stellerz.